The Derryveagh Evictions

Glenveagh Castle's Darker History

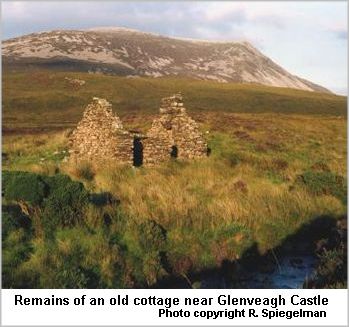

Glenveagh Castle and national park in Donegal is one of the most impressive and imposing old estates in Europe. Built in the late 1800's, it’s a favorite stop today for tourists who marvel at its turrets, its stunning view of Lough Veagh and its 40,000 acres of gardens and forest.

But there’s a darker side to the history of Glenveagh, and particularly the National Park around it, of poor tenant farmers being thrown off their land to satisfy the vanity of the castle’s owner. Over time, the tale of “Black Jack” Adair and the “Derryveigh Evictions” has become one of the most notorious stories of oppression by wealthy landlords in the history of Ireland.

Black Jack's History

Jack Adair was born in 1821 to a family in County Laois which had managed property for absentee English landlords and become successful enough to acquire its own considerable land holdings. They had followed a tradition of land agents evicting tenant farmers from property when it would benefit the owners economically.

In 1866, Adair came to America, hungry to shore up and increase his fortune in the post Civil War economic boom. He was, at the time, well off, but not rich enough to forever live the aristocrat’s life he craved. After opening a successful loan brokerage in Manhattan, he met Cornelia Wadsworth Ritchie, the widowed daughter of a wealthy family from upstate New York, at a society ball. Shortly thereafter, Adair financed the first major cattle ranch in the Texas Panhandle, which increased his wealth considerably. (The JA Ranch, by the way, is still operating.)

But sometime before 1860, Adair had already begun work in what would be his most famous – and most infamous – project. Purchasing tracts of land in the Derryveagh Mountains, he’d built up a holding of about 15,000 acres and leased even more land to create a hunting preserve for his own personal use. Taking a cue from his uncle’s service to mighty English landholders, he resolved to clear any tenant farmers off the lands he purchased. But because they were paying their rent, he was very limited in his ability to expel them.

Aftermath of a Murder

Aftermath of a Murder

Everything would change, however, in 1861, when a Scottish land steward in Adair’s employ was murdered but no one in the community could be identified as the murderer. Adair saw his chance. He invoked an obscure Norman law allowing a landlord to hold an entire community guilty where no individual could be charged, and sent 200 soldiers and police into the surrounding townlands, like Derryveagh, to throw people out of their homes. Between April 11th and 13th of 1861, a “crowbar brigade,” helped by police and soldiers, uprooted over 250 people, most of whom became destitute on the roads or inside the workhouse.

Eight months later, the local church made a deal with Adair, under which able bodied young adults were shipped to Australia, in an “assisted emigration scheme” that for many, appeared better than starving in Derryveagh. The evictions would cause an outcry in Ireland and the English Parliament, but no legal action was ever taken against Adair.

Dark Place in History

Construction on Glenveagh Castle was begun in 1867. Adair and his American wife lived as “Victorian jet setters,” traveling between fox hunts in England, entertaining guests at Glenveagh and caring for their business interests in Texas, until 1885, when Mr. Adair died of dysentery in St. Louis. “Black Jack” is today known as one of the most notorious evictors in Irish history.

This story was created with the help of Robert Spiegelman, a New York writer, filmmaker, educator and historian who has created an excellent website about The Derryveagh Evictions

Dr. Spiegelman came upon this tragic story in an interesting way. Visiting historic Kilmainham Jail in Dublin in the early 1990’s, because he “didn’t feel like visiting the Guinness Brewery and the other typical spots,” he struck up a conversation with an Irishman, who invited him to come and stay at his family’s B&B in Donegal. “I’ve got a story to tell you on the way,” he added. It was on that drive from Dublin to the northwest that Mr. Spiegelman first heard the story of the Derryveagh Evictions. He has pursued it so deeply that he currently lectures on the subject in Ireland and in the U.S., and is available for talks through his website, or at 212-222-8228.